Rhododendron minus: A colorful mystery wrapped in a riddle

November 29, 2023

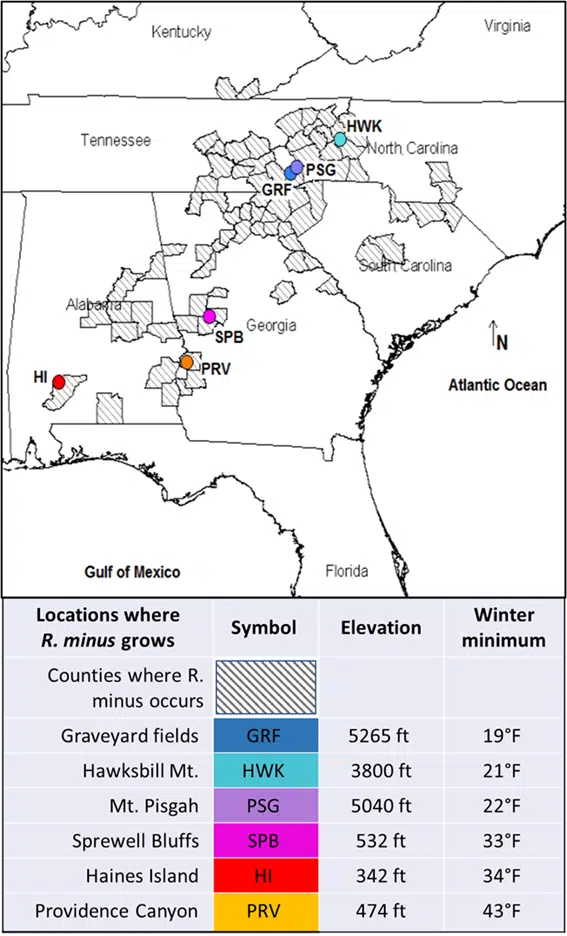

Rhododendron minus is a woody evergreen shrub native to the southeastern United States, with a range that extends from North Carolina and Tennessee south into Georgia and Alabama. Across this range, R. minus exhibits higher than average variation in traits like flower color, from deep pink to snowy white. Scientists have known for a long time that this variation exists, the mystery that remains to be solved is “WHY?”

At the northern end of its range, R. minus occurs at high elevation and regularly experiences freezing temperatures, while plants in the south occur at lower elevations and never experience frost. HF&G researcher Juliana Medeiros, PhD, investigated whether these different climate regimes might be a factor causing trait variation in R. minus. They found that the same pigments which determine flower color also play a key role in preventing winter leaf damage, showing that color variation of R. minus flowers is just the tip of a mystery iceberg. Further, this research revealed a new riddle about the interaction between pigments and a unique cold tolerance trait, leaf curling.

Gardeners know that some plants are vulnerable to frost, but even slightly chilly days can be stressful for plants. During the growing season, green chlorophyll pigments absorb light to produce sugars through photosynthesis. Temperatures below 50°F are too cold for R. minus to conduct photosynthesis, so the light energy that would normally be used for photosynthesis has an opportunity to go rogue, creating toxic byproducts that damage chlorophyll.

Another class of pigments called carotenoids can protect chlorophyll by absorbing the excess light and safely dissipating it as heat. Carotenoids are yellow and orange, and these pigments create fall color, being revealed as the chlorophyll is degraded in preparation for winter.

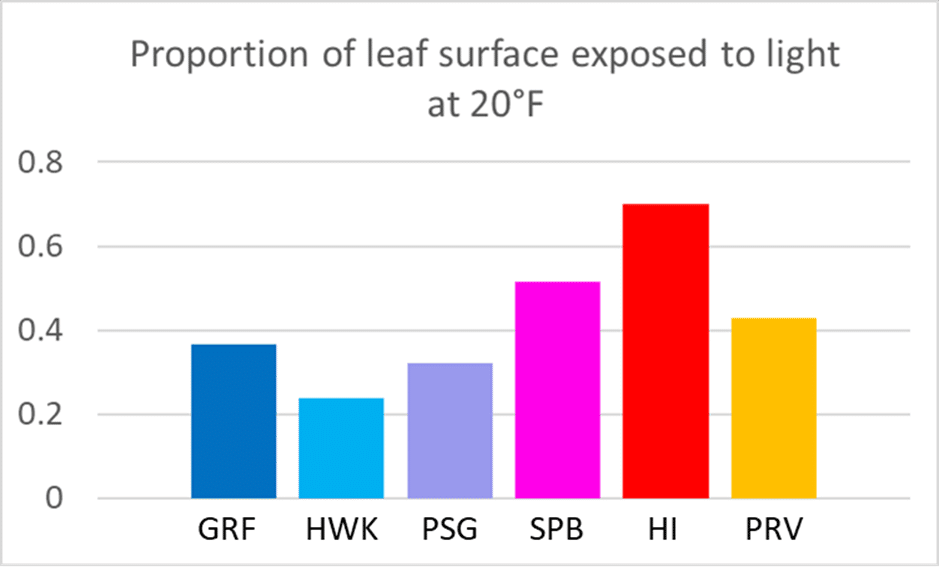

While carotenoid pigments are found in just about all land plants, R. minus has developed leaf curling as unique component of its winter toolkit, responding to cold temperatures by wrapping their leaves up into a cute little cigar-shape. This is thought to protect the leaf from desiccation by dry winter winds, but also reduces the amount of light intercepted by the leaf, helping those carotenoids do their important job and further protecting chlorophyll from light damage.

To investigate the role of pigments and leaf curling in cold hardiness, Dr. Medeiros grew plants from seeds collected at cold and warm locations and exposed them to winter conditions at the Long Science Center. This work reveals that it’s not just individual traits, but interactions between pigments and leaf curling which determine plant climate tolerance, providing unique insight into the intricacy of biodiversity, even within a single species.

They found that plants from cold northerly locations doubled down on stress resistance, employing both carotenoids and leaf curling to protect their leaves from winter damage. On the other hand, southern plants displayed weak cold response and experienced greater frost damage as a result, but they grew faster than northern plants, uncovering a trade-off between fast growth versus stress resistance. In southern locations where frost is absent, it just doesn’t make sense to spend resources on making yourself cold hardy, rather fast growth should be favored because it makes for stronger competitive ability. Thus, this study provides evidence that trait variation in R. minus has ecological relevance, plants growing in warm and cold locations have different traits that allow them to thrive in their local climate.

Variation in protective pigments was quantified in the study using analytical chemistry techniques but can be visually observed as differences in fall color. Plants from Georgia and Alabama remained green throughout the winter and did not develop fall color display. On the other hand, plants from colder locations displayed strong fall color in lower leaves, and variation among plants from the cold locations was also observed. Plants from Hawksbill Mountain had a predominance of orange and yellow carotenoids, whereas those from Graveyard fields had very bright pink fall colors derived from another kind of protective pigment, anthocyanins.

These different pigment profiles were accompanied by differences in leaf curling. Following exposure to 20°F plants from warmer locations had 40-70% of their leaf surface exposed to light, while leaves of plants from colder locations had only 20-40% of their leaf surface exposed. Importantly, the dual system of pigments and curling are deployed at different time scales, leaves can curl and uncurl in a matter of minutes whereas a change in pigments takes anywhere from hours to months. This dual system likely provides a more nuanced balance between fast growth and stress resistance than one trait could on its own.

Interestingly, anthocyanins and carotenoids are not just found in leaves, these are also the key pigments in flowers, indicating that there could be a link between variation in flower color and stress resistance of R. minus. Ongoing work in the Medeiros lab is investigating these pigments in more depth, including development of rapid screening technologies such as spectral imaging to increase the speed of discovery. The ability to measure more samples, faster is certain to shed additional light on how this colorful pigmentmystery became wrapped in a leaf-curling riddle, and further elucidate the roles of climate and trait variation in determining where R. minus grows on the landscape.

Juliana S. Medeiros, PhD

Plant Biologist

My research focuses on plant anatomical and physiological acclimation and adaptations to the abiotic environment. I am interested in how phenotypic and genetic variation in plant form and function interact with variation in climate over space and time to drive ecological patterns and the evolution of plant diversity. Research in our lab focuses on Rhododendron as a model system for the evolution of climate adaptations, with a special focus on how physiological processes and biomass allocation coordinate to determine species traits like stress tolerance or fast growth. In addition to research, I supervise research trainees from undergraduate to postdoctoral level, conducting work in plant physiological and evolutionary ecology on a variety of woody plant species. I am also passionate about scientific outreach activities, including development of a hands on teaching kit “The Drip Races” which teaches about plant water transport as a key component of woody plant biodiversity and conducting seminars on non-academic career paths.