If you are new to identifying mushrooms, I recommend that you read my earlier article, How to identify mushrooms and other fungi, for context and terminology before reading on.

Mushroom hunting can be a fun and exciting way to connect with the environment. While reading about a mushroom in a book is helpful, I have always found that I remember new species better if I engage with them on another level. This may be through making mushroom dyes (did you know some mushrooms can be used for botanical dyes?), or by making a spore print. For some individuals, however, foraging mushrooms for consumption is an important part of their relationship with food and nature. While foraging is not allowed on Holden Forests & Gardens campuses, we are happy to take the opportunity this Mushroom Month to give you a brief introduction to edible mushrooms and some of their poisonous look-alikes. The species that I introduce are all present in our Northeast Ohio forests! I will introduce each species with its common name, latin name (italicized), and a photograph.

Please Note: This article is far from exhaustive. Fungi are incredibly diverse and different species can look very similar, therefore attention to detail is critical for even the most experienced mycologist. This article is not meant to be used alone to identify fungi for food or medicine. If that is your intention, I recommend that you seek further information and guidance before taking on that endeavor. Also, as with any new food some individuals experience allergies or sensitivities to new mushrooms, so not all edible mushrooms that are safe for one individual are safe for another. I recommend trying a small amount of any species that is new to you before committing to a full meal.

Chanterelles, Cantharellus species (left) and the jack-o’-lantern mushroom, Omphalotus olearius (right)

Chanterelles (left) are often celebrated as a wonderful mushroom for a beginning forager to start with. While they are incredible mushrooms, I do not find them as “beginner friendly” as some may say. While species in Cantharellus can be distinguished by a few reliable features, I have, at times, found those features to be rather subtle. The primary diagnostic trait for Chanterelles is that their fertile surface is composed of “folds” rather than true gills (the plate-like blades on the underside of the caps of many mushrooms). The folds of a Chanterelle look more like wrinkles beneath the cap surface than the true gills of other mushrooms. By comparing the folds of the Chanterelle to the gills of other mushrooms these differences will begin to look more apparent.

Some species of Chanterelles may look relatively similar to the poisonous Jack O’Lantern Mushroom (right) save a few distinguishing features. Where Chanterelles have folds, the Jack O’Lantern has true gills. Also, where the gills of the Jack O’Lantern end abruptly all at the same spot along the stem, the folds of most Chanterelles run along the stem of the mushroom, ending unevenly at various points. These Jack O’Lantern mushrooms can cause severe gastrointestinal distress so it is important to rule them out while looking for Chanterelles. Despite being toxic, these mushrooms are an amazing find due to their slight bioluminescent feature! Late at night the gills of the Jack O’Lantern glow a soft greenish light… just in time for spooky season!

Calvatia gigantea (left) and ‘Amanita egg’ (right)

Calvatia gigantea, or the Giant Puffball, is considered edible while it’s fresh. When the exterior flesh of the fungus is firm and the inside is completely white (prior to spore development), the Giant Puffball is edible. Once the spores begin to develop in the middle of the puffball, it is too late to forage. To determine whether spores have developed, cut the puffball in half vertically and examine the color. If the interior is pure white, spores have not yet developed!

Another critical reason to bisect this species is to rule out deadly toxic look-alikes including Amanita virosa and Amanita bisporigera, amongst others in this genus. One reason why poisonous Amanita species are misidentified as edible mushrooms is because they develop from little balls that we call ‘Amanita eggs’ (right). Eventually, the mushroom emerges from the sack-like structure where it develops. These eggs protect the developing spores so that they are not eaten before they are ready to spread and grow. If you cut in half an Amanita egg, you should be able to see the faint or apparent outline of the developing mushroom. This feature can be hard to see if the egg is extremely immature, so it is important to attentively examine the cross section.

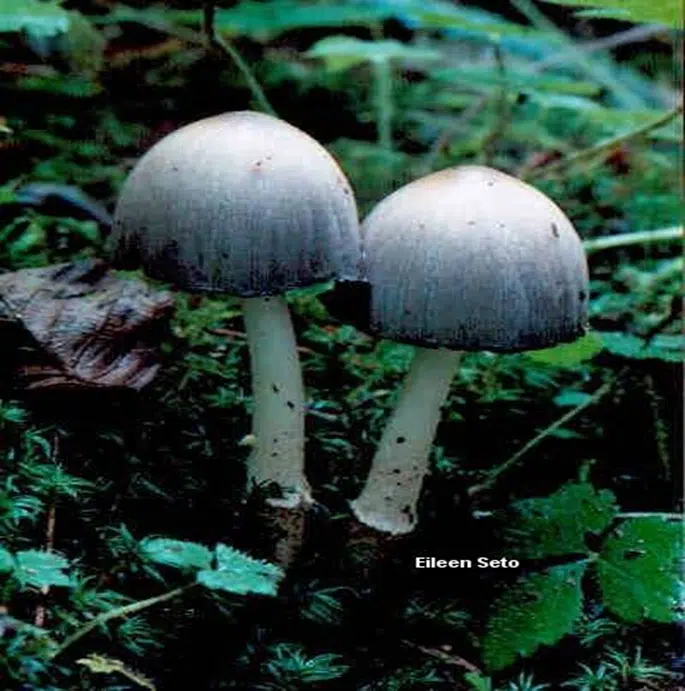

Shaggy Mane, Coprinus comatus (left) and Alcohol Inky Cap, Coprinopsis atramentaria (right)

Shaggy Mane, or Coprinus comatus (left) is a fine edible mushroom for the more experienced forager. Be aware, once this mushroom matures it begins to desiccate, becoming slimy and not very appealing. While this species does not have safety concerns of its own, it appears relatively similar to a handful of toxic look-alikes. First, Shaggy Mane should be distinguished from the “Alcohol Inky Cap”. While these species have a fairly similar shape and color, they can be distinguished from one another because the Alcohol Ink Cap lacks the same “shaggy” texture on its cap. Interestingly, the Alcohol Ink Cap gets its name because its toxic component, “coprine”, is highly reactive with alcohol. Even days before or after consuming alcohol, coprine may cause consumers headaches, extreme nausea, and a smattering of other unpleasant symptoms.

Shaggy Mane, Coprinus comatus (above) and The Destroying Angel, Amanita virosa (below)

The vast majority of mushroom related deaths are caused by species in the genus Amanita. These deaths are largely caused by mistaken identifications. A. virosa (pictured here), or the Destroying Angel is native to our region and fruits relatively often around mature trees in the forest and even in yards. The Destroying Angel is only one of many deadly poisonous species within this genus (Its relative, Amanita phalloides, has even earned itself the common name, Death Cap). Shaggy Mane is one species that survivors of Amanita poisoning have cited as the mushroom that they thought they were collecting. See this article for more information on Amanita poisoning.

The Yellow morel, Morchella americana, (left) and the False Morel, Gyromitra spp. (right)

Morchella americana, or the Yellow Morel (left), is a “true morel”, which fruits in the early spring often among hardwood trees. These edible mushrooms tend to be fun and beginner friendly due to their distinct appearance. This true morel’s poisonous look alike, Gyromitra spp., is relatively easy to avoid. Gyromitra is important to avoid because some species within this group contain a highly toxic and carcinogenic chemical called gyromitrin. While processing methods exist to rid the mushrooms of most of their gyromitrin, mistakes can lead to acute illness (https://www.aldendirks.com/1001-mushrooms). Gyromitrin, which occurs in different concentrations in different species of False Morels, affects the central nervous system and can lead to anything from nausea and convulsions to coma and death.

Luckily, Morchella species can be distinguished from Gyromitra species due to a few key features. First, the cap of the true morel is pitted, whereas the cap of the False Morel appears wavy and crumpled. Additionally, the true morel can be distinguished by its smooth hollow stem whereas the stem of the False Morel is nearly solid. As with any edible mushroom, taking the time to make this distinction is an incredibly important aspect of collection and processing.

The “half-free morel”, Morchella punctipes (left) and Verpa bohemica (right)

Morchella punctipes or the “Half-free” Morel (left) is an edible but less sought out species relative to the Yellow Morel. M. punctipes’ bell shaped cap dons the same pitted texture as its more popular relatives, but hangs “half-free” of the stem, as shown above. When collecting morels, it is important to cut each individual collection in half vertically to observe important diagnostic traits. Here, the Half-free Morel is compared to its semi-toxic look-alike Verpa bohemica (right). V. bohemica is distinct from M. punctipes because its cap hangs totally free from its stem, attached only by a small section at the very top. Additionally, its stem features a white pithy scruff, which is visible here. While V. bohemica is sold for consumption in some countries, it is known to cause gastrointestinal distress for some people, or if eaten in large portions.

Thank you for reading. If you’re interested in more mushroom related content, stay tuned for more Mushroom Month blog posts and consider registering for our upcoming Fall Foray with the Ohio Mushroom Society on September 28th!

Photo credits: Patricia Kaishian, Michael Kuo, Jillian Bastock, Micheal Bueg, Eileen Seto, Tim Gerlitz

Claudia Bashian-Victoroff, MS

Research Specialist

I am a fungal ecologist focused on connections between soil fungi and tree health. My research couples field collections with modern molecular identification methods to investigate ectomycorrhizal species diversity and function. As a research specialist in Dr. David Burke’s lab at the Holden Arboretum, I support research on soil ecology and forest pathology. Currently, I focus on the role of soil fungi in urban canopy restoration in Cleveland, OH. Trees growing in urbanized environments are subject to pressures such as habitat fragmentation, exposure to heavy metals, and soil compaction. Mycorrhizal fungi can enhance plant growth, disease resistance, and drought tolerance; therefore, it is necessary that we establish a better understanding of how these fungi might improve outcomes of urban restoration efforts. Beyond this, I enjoy discussing the importance of fungal research and conservation with diverse audiences through teaching, writing, and mentorship.