Beech Leaf Disease

What causes beech leaf disease, what you can do about it, and the latest research from the experts at Holden Forests & Gardens

Wondering what’s wrong with your beech tree?

Unfortunately, beech leaf disease is prevalent in northeastern Ohio. Affecting our native beech tree, the American beech (Fagus grandifolia), the disease is relatively new on the scene. Researchers at the Holden Arboretum are collaborating with experts across the region to better understand the disease and find effective treatments.

On this page: Treatments | Our Research | Beech Leaf Disease FAQ

Wanted: Resistant beech trees!

If you have an American beech on your property that is surviving beech leaf disease while the beech trees around it are dying, let us know! Your tree may be genetically resistant to beech leaf disease, and could play a role in our beech resistance breeding program. Reach out to our Forest Health Coordinator, Rachel Kappler ([email protected]) with information about your tree. (Please note that if you’re in a developed area, the beech in your backyard may be an ornamental European beech, not an American beech.)

Treatment options for beech leaf disease

The number one question we get about beech leaf disease at Holden is, of course, what can I do for my beech trees? Research on beech leaf disease treatments is currently ongoing. Here’s what we know so far, and our recommendations.

The latest: Beech leaf disease experts from around the region, including Dr. David Burke, VP for Science and Conservation at Holden Forests & Gardens, announced in March 2024 the long-awaited results of experimental trials of potential treatments for BLD. They found that foliar treatment of the fungicide fluopyram, when applied at the right time, kills over 90% of live nematodes. The study, led by collaborators at Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories, tested treatments including abamectin, acephate, emamectin benzoate, fluopyram, oxamyl, and potassium phosphite on infected trees in Connecticut, New York, and Ohio. The other methods tested were not effective against beech leaf disease.

Effective fluopyram application needs to occur when the nematodes are migrating out of the leaves and into the buds to overwinter, which occurs in late summer when the leaves are wet, such as after a heavy rain. This treatment won’t improve leaf symptoms in the current year, but would affect the following year’s leaf out. The study was published in the Journal of Environmental Horticulture.

Fluopyram is a harsh chemical and its application should be considered with great caution. The pesticide may kill all fungi in the application area, therefore we currently only recommend its use by professionals and in special cases. For instance, at the Holden Arboretum, we might consider treating our large European weeping beech, a critical specimen in our Main Display Garden, but would not likely apply fluopyram in any of our natural areas.

A milder option that has shown promise, though it was not included in this study, is using polyphosphite 30, a potassium fertilizer, to reduce nematode number and symptoms of BLD. The mechanism by which this works is not yet known. Many extension offices have begun to recommend this treatment to their communities.

Finally, if you have beech trees, we recommend pruning your trees to increase light and air circulation to reduce moisture in the canopy. Drying out the leaves can limit the nematodes’ life cycle and spread. Trim in winter or early spring when the trees have no leaves, or in late August/September before fall rains return.

Regular tree care such as a fall or spring fertilization treatment and proper mulch application around the base of the tree can also help support your beech trees whether or not they have symptoms of the disease.

Beech leaf disease research at Holden

Beech leaf disease was first discovered in 2012 in Lake County, Ohio, not far from the Holden Arboretum. Since the beginning, researchers at Holden Forests & Gardens have been working to understand what causes the disease and how we can fight back. BLD was discovered at Holden in 2014, and quickly swept through the arboretum’s natural areas, where American beech trees are dominant, as well as the beech research orchard at Long Science Center.

Identifying the cause of BLD

The cause of beech leaf disease was not immediately apparent until 2017, when collaborator David McCann from the Ohio Department of Agriculture found nematodes in a sample of infected beech leaves. A team led by Lynn Carta at the USDA-ARS in Beltsville and Holden’s Dr. David Burke used molecular methods called ribosomal DNA marker sequences to identify the nematodes as close relatives of Litylenchus crenatae from Japan. They named this new North American subspecies Litylenchus crenatae mccannii after McCann, and their work was published in Forest Pathology in 2020. A photo of the nematode was on the cover.

To see if the nematode was acting alone in causing the disease, Burke, in collaboration with the U.S. Forest Service, studied bacteria and fungi on leaves and buds from Holden’s beech research orchard. The team found no signs that fungi differed between symptomatic and asymptomatic trees, but bacteria communities were consistently different on diseased leaves. This important early study appeared in Forest Pathology in 2020. Later work would confirm the nematode as the source of the leaf damage, so experts suspect these bacteria are secondary infections.

Another piece of the nematode puzzle came a few months later, in another 2020 Forest Pathology study. Burke, working with a team led by the Ontario Forest Research Institute, found that the number of nematodes increases over the growing season, peaking in fall — and that nematodes are found overwintering in buds. This laid important groundwork for recent work outlining the mechanism by which nematodes cause changes in buds and leaves at the cellular level, causing the BLD symptoms.

Breeding trees resistant to BLD

While researchers in the Burke lab work to understand beech leaf disease, other experts at Holden are working to fast-track solutions. The Great Lakes Basin Forest Health Collaborative is leading the charge to save beech, as well as ash and hemlock, by uniting efforts across the region to breed pest-resistant trees. Led by Forest Health Coordinator Rachel Kappler, their base is at the Holden Arboretum.

It’s become clear that some beech trees, even in highly affected areas, develop little or no symptoms. This means they have some level of genetic resistance to beech leaf disease. The GLB FHC is coordinating efforts to locate these trees, test them for resistance, and breed them for eventual replanting efforts. If you have a potentially resistant tree, tell us! Reach out to Rachel Kapper ([email protected]) with information about your tree.

When we identify a potentially resistant tree, with the landowner’s permission, we may take a cutting and bring it back to the greenhouse at the Holden Arboretum. There, we graft the branch onto a healthy rootstock growing in a pot, which allows us to run tests on it. We’ll test these grafted trees — genetic clones of the trees out in nature — with nematodes to see if they really are resistant. If they are, we’ll incorporate them into our long-term breeding program in hopes of using them for future forest restoration all across the affected region.

BLD research continues

While the GLB FHC works toward BLD-resistant beech trees, research into the causes, consequences, and potential treatments for beech leaf disease continues at Holden. In April 2023, Holden researchers found a new downstream effect of the disease: The roots of infected trees have fewer helpful fungal mutualists called ectomycorrhizal fungi. That’s bad news for both the trees and for the fungi species they support. Their work is published in the Journal of Fungi.

Also in 2023, researchers in the David Burke lab developed an improved, effective way to monitor and detect the presence of the disease-causing nematode in beech leaf tissue. The new tool uses a long-standing laboratory method that can be used to detect DNA specific to a certain organism. Previously, forest health professionals looking for the nematodes would have to undertake a slow process that involved soaking leaves for twelve hours, further preparing samples, and then looking for nematodes under a microscope — not something that could be done at large scales. The new method is detailed in the journal Plant Disease.

Beech Leaf Disease FAQs

What does beech leaf disease look like?

The main symptoms of beech leaf disease are green stripes, called interveinal banding, on the leaves and sometimes thick, leathery, or even stunted-looking leaves. Note that yellow or red spots on beech leaves are signs of other diseases, not BLD.

Can I proactively protect my trees from beech leaf disease?

There is no way to prevent beech leaf disease from spreading to your trees. We recommend strategic pruning to reduce moisture in the tree canopy, especially before fall when the nematodes spread (see “treatment options for beech leaf disease,” above).

Should I cut down my beech trees?

No, and especially not proactively (that is, before you see symptoms of beech leaf disease). Your beech trees may be resistant to the disease and may survive. Resistant trees are also valuable, as we can use them for breeding selection programs with the U.S. Forest Service. Of course, if your tree has seen serious decline and is posing a hazard, then it should be removed. An arborist can help with that decision.

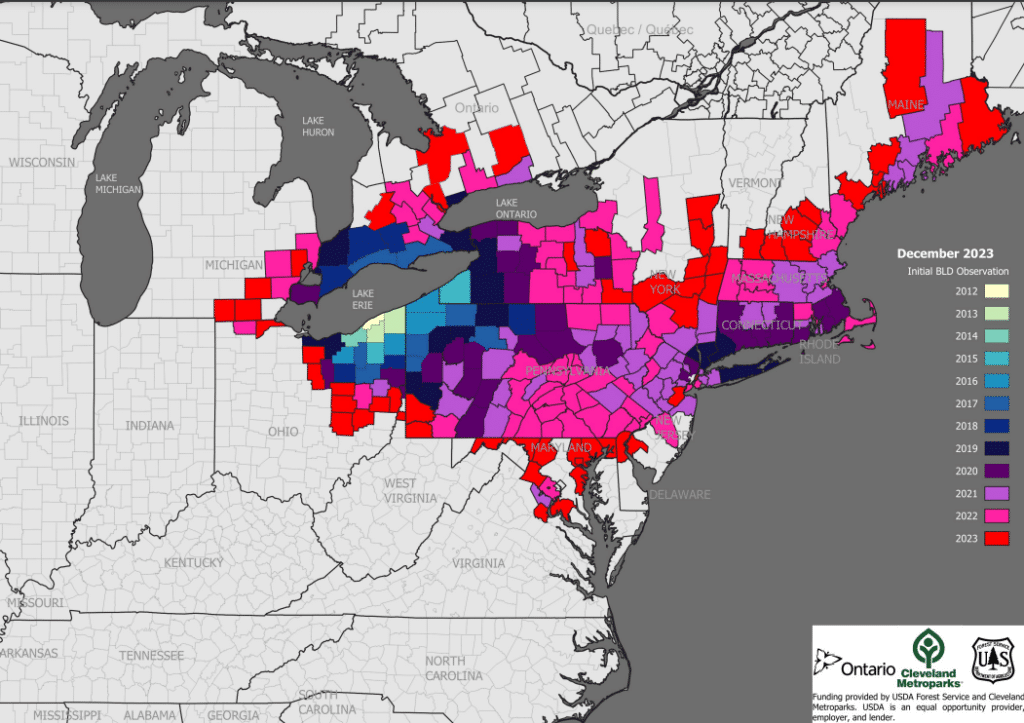

How far has beech leaf disease spread?

Beech leaf disease is an emerging threat to North American forest ecosystems. Symptoms of the disease were first discovered in northeastern Ohio in 2012, and it has already spread to Michigan, Ontario, and as far eastward as Maine and Virginia.

What causes beech leaf disease?

Beech leaf disease is caused by an invasive nematode, Litylenchus crenatae mccannii, which was first discovered in 2017. Nematodes are microscopic, wormlike animals that are small enough to live inside leaves and buds of trees. The nematodes enter the tree’s buds and feed on tissues inside over the winter, which causes the damage to the leaves.

What trees can be affected by beech leaf disease?

Our native American beech (Fagus grandifolia), along with common ornamentals European beech (F. sylvatica), Oriental Beech (F. orientalis), and Chinese beech (F. engleriana) are all affected by beech leaf disease. At this time it seems Japanese beech (F. crenata) may be resistant. Researchers have detected signs of the nematodes on other trees, like maple trees, but those trees haven’t shown any sign of disease.

What beech trees are safe to plant?

For now, we don’t recommend planting any new beech trees.

Are the beech trees getting any better?

We’ve noticed variation in the severity of symptoms on some trees from year to year, which in a good year can appear as if the trees are getting better. We’re not yet sure what causes this variation, but suspect it has to do with weather conditions in the fall, when the nematodes are moving from leaves to buds. We would expect a drier fall to be harder on the nematodes, resulting in fewer beech leaf disease symptoms the following season. When this happens, the trees aren’t so much “better” as getting a break from the nematodes’ damage for the season.

Can I help document healthy or diseased beech trees?

Yes! The best way to submit an observation of an American beech tree is through the free app TreeSnap. Take photos of the leaves, bark, and other identifying features so experts can confirm your beech identification, and make sure symptoms are visible if you’re submitting a sick tree. It’s especially important to report healthy trees in otherwise-affected areas. These healthy beech trees might be resistant to BLD and could be used to breed resistant trees for replanting. You’ll submit photos and other information about your observation right in the app. To report a healthy American beech, you can also reach out to our Forest Health Coordinator, Rachel Kappler, directly ([email protected]).

How is beech leaf disease different from beech bark disease?

Unfortunately, there are not just one but two major pests — beech bark disease and beech leaf disease — bothering our region’s beeches. Beech bark disease is caused by a fungus-insect duo that can girdle a tree and result in its death. First the scalelike insect Cryptococcus fagisuga pierces the bark to feed. Then, that damage allows the canker fungus, Nectria spp., to move in and kill the tree. Many mature beech in the northeastern U.S. have already been lost to beech bark disease.

Need help with a beech tree on your property?

If you have a beech tree on your property and would like advice from an expert, we recommend reaching out to a local tree care company. However, do remember that this is an emerging disease — even the world’s experts are still trying to figure out the biology of how it works, which means recommendations for how to treat it may update quickly.

Contact us

To report a resistant beech tree, please contact:

Rachel Kappler

Forest Health Coordinator

[email protected]

General inquiries please contact:

Anna Funk

Science Communications Specialist

[email protected]