What’s the (Compost) Tea?: Hot-and-Bothered by the Cold Brew

January 20, 2022

By: Rob Maganja, Horticulturist

Compost tea is one of the mythological potions of horticulture. I can just imagine bottles of it on the refrigerated shelf in Whole Foods, somewhere between the kombucha and the kefir. There’s about a million words in tiny, tiny print on each bottle. With different fonts and wild claims and maybe even a Biblical quote or two.

The boldest of the claims are that:

- It restores bacterial community diversity both on foliage and in soil.

- It increases soil water retention, and thus, it can be used in place of watering.

- It decreases the need for fertilizers.

- It works faster than compost, and it also reduces the amount of compost you use.

- It helps to reduce pressure from both pests and phytopathogens.

I’m not here to say that any of those claims are wrong. In fact, after doing plenty of research, I don’t know if anyone can fully dispel any of those claims. But, I can say that the horticultural world is definitely divided as to what to think of compost tea.

Ambivalence towards compost tea was definitely something I felt when I worked at Philadelphia’s Longwood Gardens. One of my duties as the Integrated Pest Management intern was to brew 100 gallons of compost tea at least every other week. But, despite the massive size of Longwood—over 1,000 acres of grounds, including 4.5 acres of greenhouses—only three horticulturists used the tea. Additionally, my boss was pretty on-the-fence about its effectiveness, so I didn’t even bother researching it for myself.

But, on my end, brewing the tea was quite a time commitment.

The process started with mixing compost with fish emulsion, and then putting that mixture into a tray to sit for a day or two. After that time, a significant amount of beautiful, white, wispy fungal mycelium growth was present.

That mixture was then placed into a large “tea bag” and hung from the lid of a 100-gallon tea brewer. Non-chlorinated water was added, and then I added kelp and more fish emulsion to act as food for the microorganisms. The final step was to hook up a motor-powered aerator, which was left on for a full 24 hours.

After the 24 hours were up, each of the horticulturists who used the tea came to pick it up with an electric cart outfitted with a tank on the back. Because the brew is very time-sensitive, they’d use it as soon as possible (oxygen-dependent microorganisms begin to die or eat each other only a few hours after their source of oxygen is gone).

For some reason, all the horticulturists who used it were based in glasshouses, like the DuPont House and the Rose House.

And the horticulturist of the Rose House, for example, sprayed the tea as a foliar application, to prevent fungal diseases from attacking his roses.

The cost and time associated with making compost tea is kind of daunting. For a place like Longwood, it’s a drop-in-the-pan, but those are considerations that definitely need to be taken into account for the average home owner.

But, most importantly, does this thing actually work?

Let’s start with the facts:

- Compost tea is never for human consumption. In fact, because the process begins with oftentimes unregulated compost, there’s a risk of deadly pathogens like E. coli, Salmonella, and Listeria being present in the final brew—especially if the compost had animal manure in it and it wasn’t properly heated to 131° F.

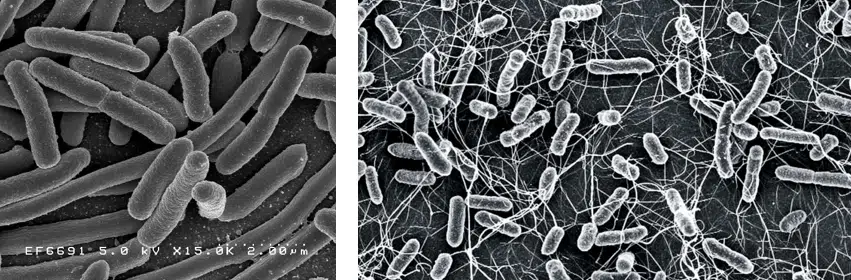

Photo Credits: National Geographic Society and Futurity

- 2) Compost tea can be aerobic or anaerobic. The main difference is that aerobic tea requires a constant influx of oxygen during the brewing process to aid with microorganism growth. A food source is also added, so that the microorganisms can feed. Food is not generally added to an anaerobic tea, because, if the microorganisms ate all the food, they’d balloon in numbers, but then there’d be large die-offs due to lack of oxygen (going forward, I will refer to aerobic tea as “aerated compost tea” and to anaerobic tea as “compost extract”).

- 3) Especially if you’re making an aerated compost tea, timing is everything. Many tea recipes involve aerating for 24-48 hours—but at that point, the brew must be used. If not used within a few hours, large losses of microorganisms will start occurring.

- 4) You can make a fungal-dominant tea or a bacterial-dominant tea, depending on what types of plants you’re growing—typically bacterial for annuals, and fungal for perennials, shrubs, and trees.

Photo Credit: Quadra Island Garden Club

- 5) As is, compost usually has much less Nitrogen-Phosphorus-Potassium (NPK) value when compared with synthetic fertilizers. So, both aerated compost teas and compost extracts have a fairly insignificant amount of NPK, because they’re literally watered-down compost.

How they work:

If poured into the soil as a drench (the preferred method for applying compost extract):

- When you do an extraction, you pull out 100% of the diversity of microorganisms present in the compost.

- They start off dormant, and then the plant roots decide which microorganisms it wants to “turn on” and use.

- When they’re turned on, the microorganisms grow, breed, attract predators, eat prey, or go dormant again. (Joel Williams)

- The microorganisms create protective barriers around the roots, they release nutrients when they die, and they create and improve soil structure. (Lowenfels)

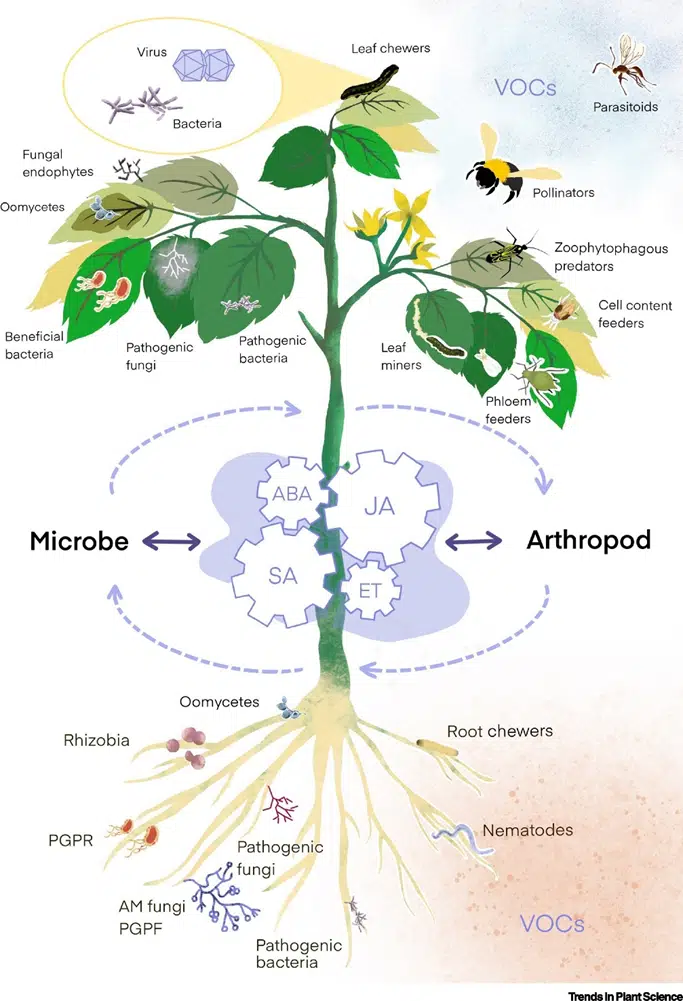

If sprayed onto the leaves as a foliar application (the preferred method for applying aerated compost tea):

- The increase in microorganisms on the plant’s surfaces protects the plant and feeds it through processes like nitrogen fixation.

- In turn, the microorganisms release compounds that turn the plant’s immune system on, thus strengthening its disease resistance.

- Because the process to create the aerated compost tea involves oxygen and food sources, specific microorganisms were naturally favored to proliferate.

- Thus, when those microorganisms are sprayed onto the foliage, they’re already active and ready to combat pathogens that land on the leaves. (Joel Williams)

Photo Credit: Trends in Plant Science

And then we’ve got to consider the negatives:

- There’s a significant lack of scientific evidence to support its effectiveness, in large part because it’s so difficult to ascertain the interactions between the myriad of microorganisms present in each brew and how they might affect the plants.

- Recipes vary so much from one brewer to the next, so this lack of standardization only adds to the amount of variables at play. Add to this the multitude of compost sources, dilution rates, application rates, and application frequencies.

- Aerated compost tea and compost extract are both unregulated, and there is serious potential for them harboring harmful pathogens, especially if used on a food crop and you don’t wait the requisite 120 days before harvesting said crop. (Compost Tea 101)

- Using aerated compost tea or compost extract to inoculate new soil with beneficial microorganisms doesn’t make sense, because, if you provide good habitat, the microorganisms should come anyway. Also, you could be doing more harm than good and create an unbalanced soil ecosystem. (Does Compost Tea Work?)

- Composted mulch has been documented to suppress many soil-borne diseases through a variety of methods (housing beneficial microorganisms, reducing splash dispersal when compared with bare soil, etc.), while neither aerated compost tea nor compost extract has scientifically documented effect as pathogen suppressors. (Chalker-Scott)

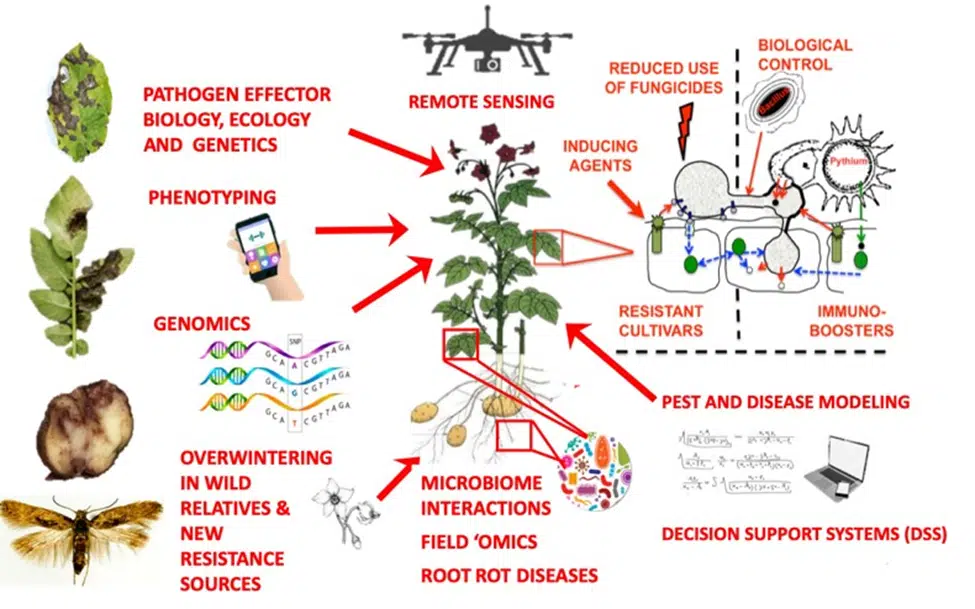

Integrated disease management projects, of which compost tea should be one.

Photo Credit: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

The Verdict:

If you have the time and money, and you can do pathogen-testing, give aerated compost tea or compost extract a go. But, conduct your own experiment and monitor results of tea usage versus no tea usage. Beforehand, send in samples of soil and leaf material to determine microorganism levels at the onset. And keep checking them for their microorganism content over time. And really take a pinpointed approach to brewing a tea that will specifically combat specific pests and diseases of whatever crops you have.

And make sure your brews adhere to a specific recipe, and apply them on a regimented schedule. Also, make sure you’re allowing the plants to properly absorb the tea—the runoff could contribute to water pollution and waste your time and money, to boot. Inadvertently, you might find that this microfocus on “watering” was what your plants were missing all along.

There’s no silver bullet for plant health problems caused by poor soil health and improper plant selection and management. Until much more empirical data comes out about compost tea, it should be used in an integrated approach, amongst other tools like genetic disease resistance, fertility and water management, and disease and pest forecasting. (St. Martin)

So, happy experimenting! And, stay tuned as we at the Holden Arboretum work to develop a compost tea that will help in our integrated management of our Rhododendron and Azalea collections.

Works Cited

Chalker-Scott, Linda. “The Myth of Compost Tea Revisited: ‘Aerobically-Brewed Compost Tea Suppresses Disease.’” Washington State University, Mar. 2015, s3.wp.wsu.edu/uploads/sites/403/2015/03/compost-tea-2.pdf.

“Compost Tea 101: What Every Organic Gardener Should Know.” Cooperative Extension | The University of Arizona, uploaded by The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension, 26 Apr. 2018, extension.arizona.edu/pubs/compost-tea-101-what-every-organic-gardener-should-know.

“Does Compost Tea Work? Part 2 Fertilizer, Beneficial Bacteria and Big Vegetables.” YouTube, uploaded by Alberta Urban Garden Simple Organic and Sustainable, 18 Mar. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=xdkhEJr3x1I.

“Joel Williams – ‘Making Compost Tea’ – Biological Farming Conference 2018.” YouTube, uploaded by National Organic Training Skillnet, 14 Feb. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=9wZARVw9Tj8.

Lowenfels, Jeff, and Wayne Lewis. Teaming with Microbes. Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

St. Martin, Chaney C. G. “Potential of Compost Tea for Suppressing Plant Diseases.” CAB Reviews, 2014, www.researchgate.net/publication/271825486_Potential_of_compost_tea_for_suppressing_plant_diseases.