New Study Reveals How Beech Leaf Disease Disrupts the Forest Ecosystem

December 19, 2025

As beech leaf disease continues to sweep across our region, the longer-term effects of the disease are starting to reveal themselves in the epicenter — right here in Lake County. Beech leaf disease was first found not far from the Holden Arboretum in 2012. And although we wouldn’t ever have wished this upon our beech trees, it is rather fortunate that the disease dropped in on a place that was already conducting long-term ecological research on beech trees and forest health.

A new study from the ecologists at Holden Forests & Gardens shows that beech leaf disease doesn’t just harm trees, it’s also altering one of the fundamental processes that keep forest ecosystems healthy: decomposition. The research, recently published in Ecology & Evolution, shows that leaves infested with beech leaf disease decompose significantly faster than healthy leaves. The findings suggest that BLD could have major downstream effects on carbon storage, nutrient cycling, and even communities of soil organisms in beech forests.

“Out in the field, we had been seeing the beech leaves falling early in the summer or laying on the ground from previous years, and could see the BLD symptoms on them really clearly,” says Brianna Shepherd, Research Specialist in the Stuble lab at HF&G, who led the new study. “It got me wondering whether they’re decomposing at different rates than healthy leaves — because if they are, that would open up a lot of questions about what that means for nutrient cycling, and carbon cycling, and ecosystems as a whole.”

Leaves Breaking Down

The decomposition of leaves may not be the most exciting facet of a forest ecosystem (debatable!) — but it’s crucial to a forest’s functioning. It’s these leaves breaking down that releases nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus back into the soil, feeding the next generation of plants and fueling the trees above.

Ever since beech leaf disease, caused by a microscopic nematode called Litylenchus crenatae subsp. mccannii, was first discovered in Ohio, it has spread across 15 states and into Canada. The disease causes thick, crinkled leaves and distinctive dark banding between leaf veins. Around Holden, tree mortality rates have reached 30% in the first decade after infection.

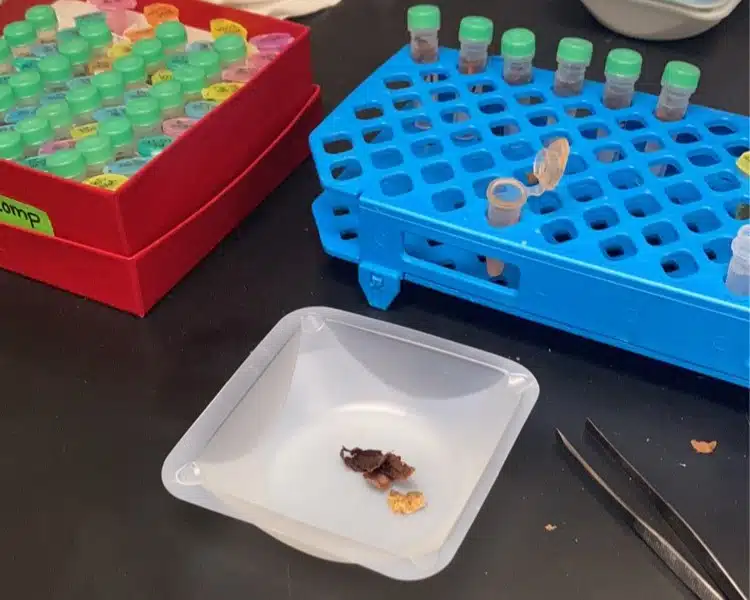

Given how dramatically BLD changes leaf characteristics, Shepherd and her colleagues suspected it might also change how those leaves decompose. To find out, they collected both symptomatic and healthy beech leaves, placed them in mesh “litterbags,” and placed them on the forest floor at two sites at the Arboretum. Over the course of nearly a year, they periodically retrieved bags to measure decomposition progress and analyze the fungal communities colonizing the leaves.

Faster Breakdown, Different Fungi

The team initially suspected symptomatic leaves would decompose slower than healthy ones. Heavily diseased leaves can become thick and leathery, and broadly speaking, thicker leaves tend to take longer to decompose. But their study revealed that in the case of BLD, the opposite was true: Symptomatic leaves actually decomposed noticeably faster than healthy leaves. The trend was apparent from the very first sampling, after the leaves had spent just 12 weeks on the forest floor.

Chemical analysis revealed why this might be: Symptomatic leaves had a lower carbon-to-nitrogen ratio than healthy leaves. Fungi and other decomposers preferentially colonize leaf litter with low C:N ratios since it makes for better food for them.

The team also found that fungal communities on symptomatic and healthy leaves were distinctly different. Most notably, saprotrophic fungi — primary decomposers — were significantly more abundant on diseased leaves. These fungi are the workhorses of decomposition, breaking down dead organic matter and releasing nutrients.

Ripple Effects

So what does faster leaf decomposition mean for forests dealing with BLD? Previous research from Holden has documented significant tree mortality from the disease. Since trees breathe in carbon dioxide and use the carbon to grow, over time, fewer living trees will mean less carbon is being pulled from the atmosphere. Meanwhile, faster leaf decomposition means the carbon stored in leaf litter is released back to the atmosphere more quickly.

“It’s nothing like the scale of carbon emissions from human industries,” Shepherd notes, “but it all adds up. Carbon from forest diseases like BLD is another piece of the broader picture — especially when you’re talking about a species as dominant and widespread as American beech.”

This study represents one of the first looks at how BLD affects ecosystem functions beyond the trees themselves. While much of the research on BLD has focused on the nematode, treatments, and tree mortality, this work reveals how the disease ripples through interconnected forest processes. As BLD continues to spread across the eastern United States, understanding these ecosystem-level impacts will be crucial for managing the long-term consequences for North American forests.

Citation: Shepherd, Brianna L., Sarah R. Carrino‐Kyker, David M. Jenkins, David J. Burke, and Katharine L. Stuble. 2025. Beech Leaf Disease Associated With Changes in Litter Decomposition and Fungal Communities. Ecology and Evolution 15.12: e72563.