What’s That Thing on the Emergent Tower? HF&G Tests New Forest Pest Monitoring Tool

November 11, 2025

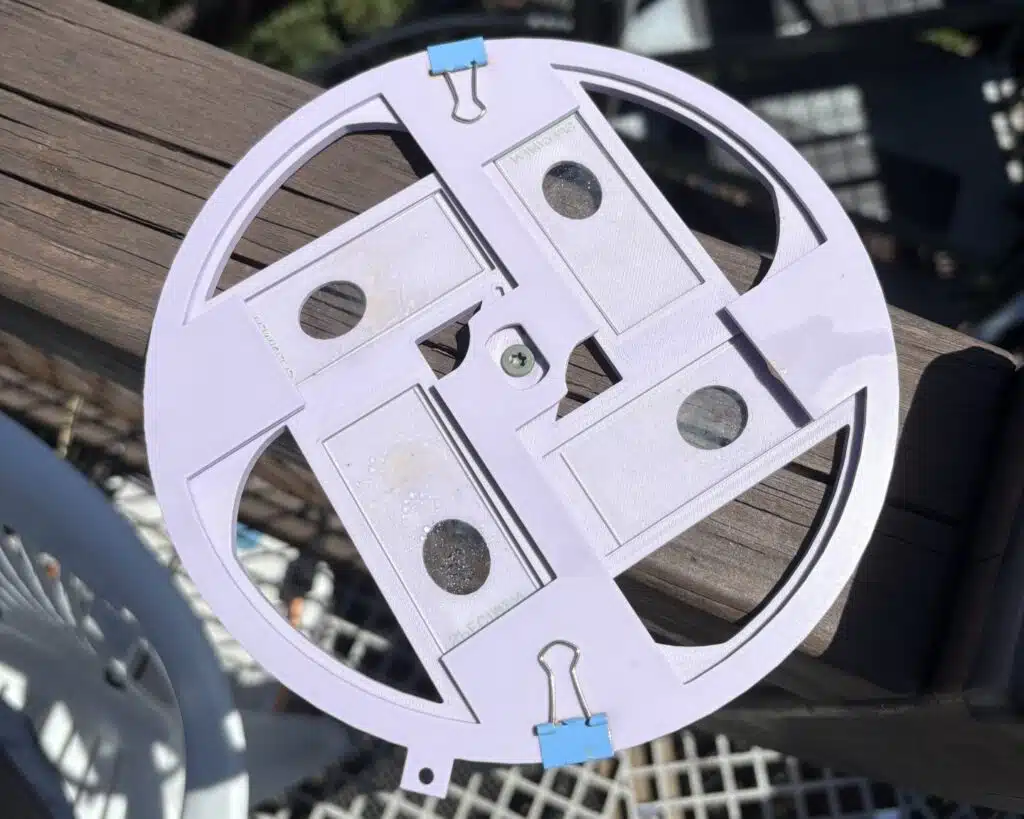

If you’ve been to the Kalberer Emergent Tower at the Holden Arboretum lately — let’s be honest, who hasn’t (#fall) — you may have noticed something new: A pale purple plastic disk mounted on the inner railing of the top platform. What is it?

The disk is what’s called an eDNA trap, and it’s a new kind of forest pest monitoring tool that Holden’s researchers are testing out. If it works, the 3D-printed plastic disk will be used to detect the presence of forest pests, like hemlock woolly adelgid or the nematode that causes beech leaf disease, before symptoms start appearing on trees. Early detection can be critical in protecting our forests from these threats.

A New Approach to Biodiversity Monitoring

Have you ever heard that the dust in your home is made of your family’s skin cells? Luckily that gross factoid is only partly true — house dust does contain a lot of sloughed-off human cells, but also tiny bits of fibers, houseplants, and all sorts of other materials from around your home.

Out in nature, this kind of “dust” exists too, but it’s coming from all the different organisms that live there. In recent decades, researchers have found that these particles, floating through the air, contain enough DNA from the source organisms that they can be used to identify which species are present in an area. It’s called environmental DNA, or eDNA for short.

In fact, earlier this year, a team out of York University in Toronto found that existing air quality monitoring systems across the United Kingdom gathered enough eDNA in their samples to identify over 1,100 different species — a truly comprehensive survey of all the life forms in the country.

Closer to home, a research team from Grand Valley State University in Michigan compared eDNA sampling methods with more traditional monitoring techniques for hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), and found they were comparable. To collect their samples, they developed a 3D-printed trap with HWA in mind, basing their idea off a fungal spore trap from researchers at the University of Florida. It’s this model that Holden’s researchers are now testing at the Arboretum.

How It Works: Capturing DNA in Vaseline

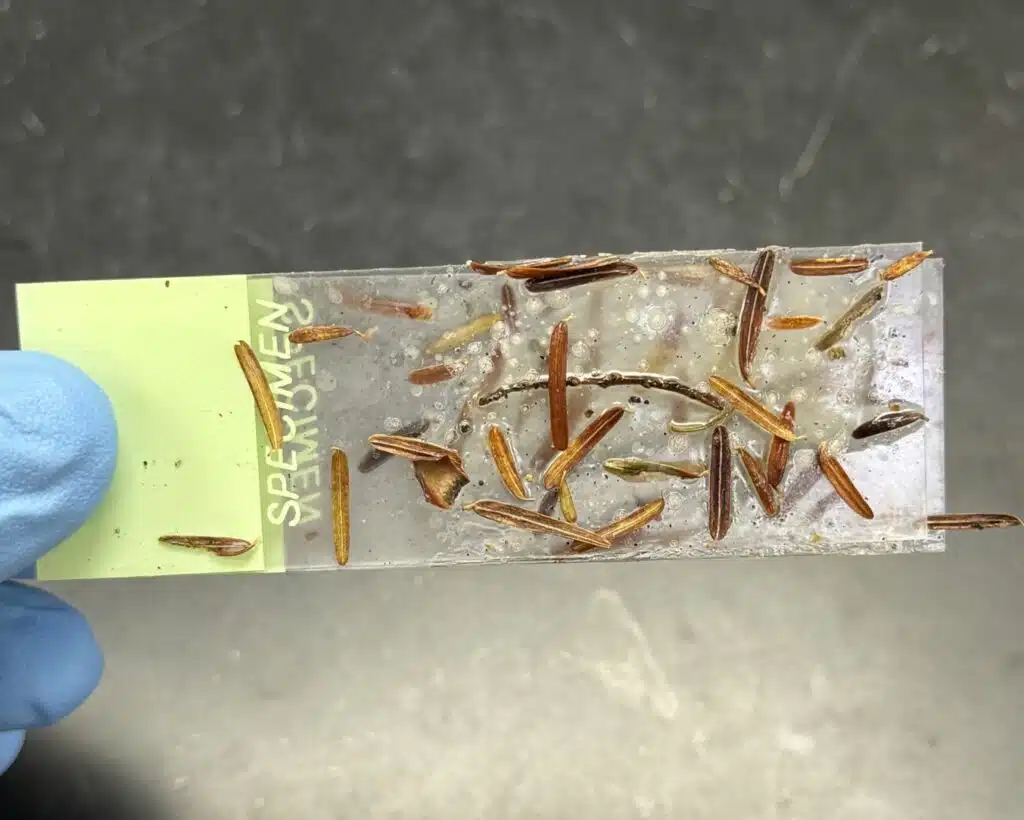

The disk itself is made of 3D-printed plastic, and it has four slots that hold microscope slides. Each slide is coated with petroleum jelly like you’d buy at the drug store. When tiny traces of organisms float by in the air, they stick to the jelly.

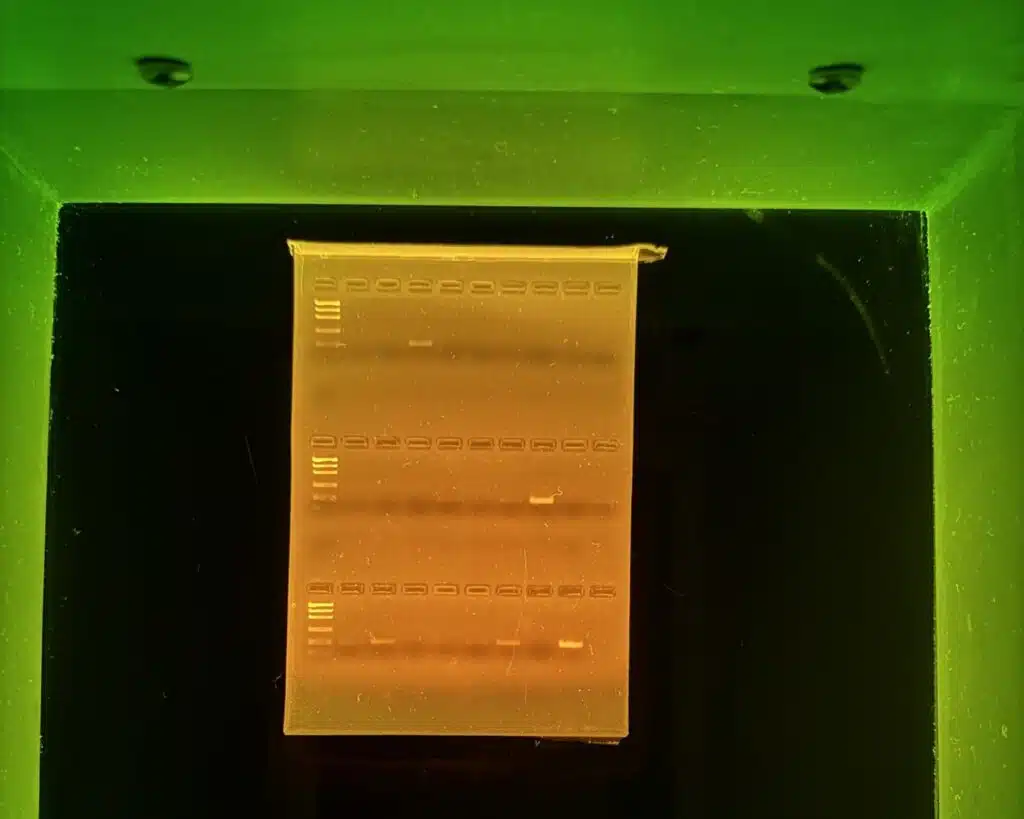

The disk itself can stay installed, and researchers can swap out the slides to check their samples. Back at the Arboretum’s Long Science Center, researchers can extract the eDNA from the jelly, looking for a match with the DNA of species of interest, like the nematode that causes beech leaf disease, hemlock woolly adelgid, or even spotted lanternfly.

David Burke, VP of Science and Conservation at Holden Forests & Gardens, explained that this type of eDNA monitoring is becoming more and more common. For instance, scientists are using it to track invasive Asian carp in the Great Lakes.

“Just because the DNA is there doesn’t mean the organism is there,” Burke cautions. “But when you’re searching for a pest, it significantly narrows down the area in which you have to look.”

Still in the Testing Phase

HF&G researchers have deployed ten of these traps across their properties: in Stebbins Gulch, Pierson Creek Valley, Little Mountain, and high up on the Emergent Tower. Most of the traps are five or six feet off the forest floor, mounted on a pole or fencepost. But the researchers also wanted to see whether signs of forest pests turn up above the canopy, on the Emergent Tower.

“We thought it would be interesting to look way above the tree line,” says Burke. “With air circulation and bird movement, maybe the trap would detect pests differently way up there.”

Burke says they’re still in the trial phase. “We’re trying to see if this works for us, and if it does, great — then maybe we’ll deploy these more widely,” he says. “If not, we’ll look at different methods.”

The traps were deployed in June, and haven’t found much yet. Burke explains that summer might not be the best time of year to detect pests like the BLD nematode (which disperses in fall) or HWA (which disperses in spring).

Maris Hollowell, research specialist in the Burke Lab, reports she got her first hit this week: the BLD nematode was detected on the eDNA samples from Stebbins Gulch. It’s an important proof of concept that shows the methods are working, even if they haven’t turned much up — yet.

Why This Matters for Our Forests

If these forest pest monitoring traps prove effective, they could become a valuable tool for protecting forests across the region. Burke envisions deploying them widely to track the spread of hemlock woolly adelgid in particular, which has been found at several sites around Northeast Ohio in recent years.

“We know that it’s present in our region, and that it’s been moving more in the last several winters since they’ve been so much warmer,” he explains. “How widely distributed is it now? We don’t know. Is it something that we need to be more concerned about in terms of the loss of our hemlock trees?”

The key advantage of eDNA monitoring is early detection. “Better to find the presence of the pest than wait for the trees to be in severe decline before you try to take some action,” he says.

Visit and Learn More

The Emergent Tower remains open to visitors this fall, so be sure to notice the purple eDNA trap affixed to the inner railing. It’s a nice reminder that HF&G properties serve as both public gardens and active research sites. While researchers work to understand whether this approach can help protect our forests, you can enjoy the spectacular fall foliage views from 120 feet above the forest floor.

Anna Funk, PhD

Science Communications Specialist

Anna Funk is the Science Communication Specialist for Holden Forests & Gardens. She earned her Ph.D. studying prairie restoration before leaving the research world to help tell scientists’ stories. Today, she wears many hats, working as a writer, editor, journalist and more — anything that lets her share her appreciation of science and its impact with others.