Thick, tangled foliage. Stems teeming in the order of thousands per square meter. A seeming chaos of new growth. To a human, these places are an unnavigable mess of saplings and thorny shrubs. To insects, birds, and mammals, these are essential habitats.

Dense habitats of native trees, shrubs, and forbs under 20ft or so are young forests. Terms for young forest you may have come across include ‘early successional habitat’ and ‘scrub-shrub’. While ecologists and practitioners have valuable arguments for splitting definitions into different terms, the essence of this ecosystem type is change… young forest is a liminal state in between meadow and older forest which is made possible by disturbance followed by a ‘rest period’, sometimes as simple as the ceasing of mowing activity. Ecosystems are dynamic and that is especially apparent in the early stages of succession from grassy or weedy areas to shrubby, pre-forested habitats. So, let’s pause on this successional threshold for a moment in the ‘in-between’ and examine this often overlooked but crucial young forest ecosystem.

Why are young forests critical habitat?

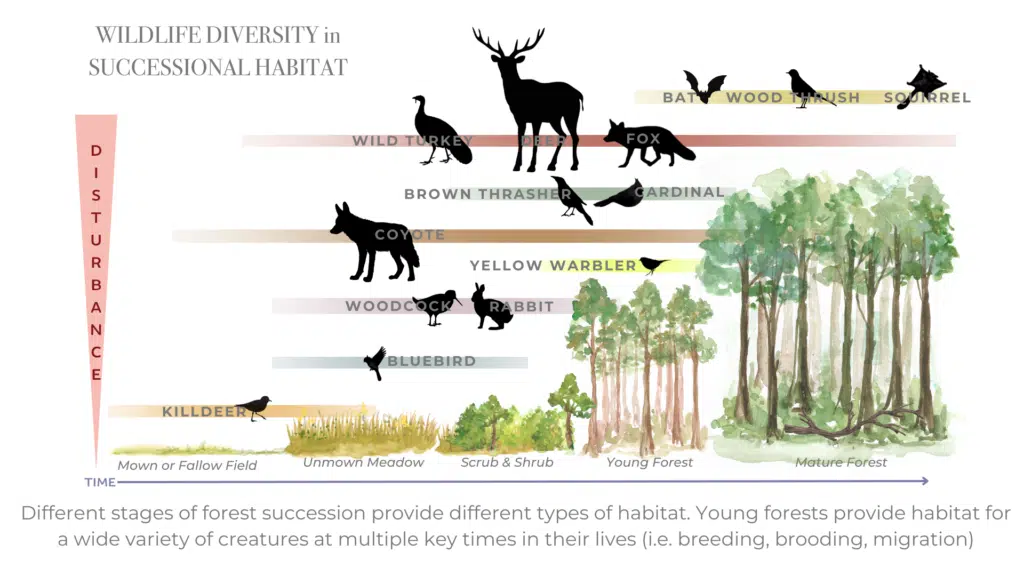

Young forests and shrublands are sanctuaries, nurseries, and pantries for wildlife. The varied structure of a complex of branches and stems provides ideal cover for animals such as rabbits, woodcock and blue-winged warblers. The high availability of sunlight means a boom of resources for growth and fruiting for a variety of plants, which in turn means excellent conditions for insect and fruit-eating songbirds. Some species specifically utilize these spaces during breeding season or to rear young. Ruffed grouse, once found in Northeast Ohio, are an example of such a species that directly depends on both scrub-shrub habitat of very young forest and have declined in numbers as this habitat has decreased, making them a species of concern in our state.

The State of Early Succession

Young forests are declining in cover area and health in Ohio. This may be attributed primarily to the boom of post-agricultural woodlands in our state reaching ‘awkward teenagerhood’ as potentially re-foresting land is often converted for development or invaded by exotic plants. Meanwhile, many maturing forests in Ohio have closing canopies and disturbance has been suppressed. Although the word disturbance may conjure negative connotations, this is an ecological term for natural phenomena such as periodic fire, flood, or windstorms. In short, disturbances are events that eastern forests have evolved with and need to regenerate. Some forest types such as oak-hickory need significant light resources early in life to achieve dominance—disturbance at the ‘right’ time is just the ticket.

The suppression of disturbance events can be bad news not only for forest regeneration, but also for animals such as the Kentucky warbler, which is in decline as canopy closure in older forests means a reduction of necessary habitat. On the other hand, some effects of ecological disturbance in the Anthropocene (this current time where humans have an outsized impact in the ecological community) are unintentional and just plain… disturbing. The ‘open canvas’ effect of a disturbance event can be a stressor in already stressed landscapes where forests are fragmented, and invasive plants often win out when given a foothold in early successional spaces. Add to this the effects of past land use and you may get something like this common scenario:

A Common Story in Ohio

Imagine a plot of land in Northeast Ohio that was used as crop field or pasture from the mid-1900s until 1980. Decades of activity on the soil have changed its physical and microbial composition and depleted the native seed bank (native seeds that remain in the soil for many years). The farm is sold, and the next landowner doesn’t mow the pasture; the neighboring maple and ash trees blow in seed and birds fly over and deposit seed they have eaten from nearby buckthorn, multiflora rose and dogwood bushes. All these species start germinating and growing together and the mix of invasive shrubs and native shrubs and trees provides some habitat for insects, birds, and wildlife that benefit in part, but the whole system isn’t as biodiverse as it could be. Invasive shrubs thrive in the poor soils without much seedbank while more slowly dispersed or other native plants cannot get a foothold.

The biodiversity and habitat quality of this scrub-shrub habitat 35 years after disturbance will not be as high as it could be and pose an issue with the amount of invasive plant fruit that continues to thrive and be dispersed, causing similar issues elsewhere. This would-be forest is unhealthy and will not become a healthy young, mid-successional, or mature forest without intervention because it is still experiencing the effects of land use from 100 years previous. The impacts of past land use, current land use patterns across the landscape, and invasive species on early successional forest are profound, meaning that the quality of the food and habitat for native-plant dependent animals is significantly decreased. While this is a conundrum, it is also an opportunity. It’s worth pausing at this point in the story to be clear: past land use is a fact, not an accusation—humans cannot help but have an impact on the landscape. Perhaps rather than pointlessly railing against unintended consequences or languishing in the myth that people are separate from natural systems, we can consider the past in the present to determine what course we want to take interacting with the landscape in the future.

The Upshot

How can we to transform a multiflora-rose invaded pasture into young forest a mother turkey may want to bring her poults into? Or how and where could we intentionally create a light gap for young forest in a closed canopy forest? What does it take to intervene at the right time to allow young forest habitat to thrive? These are questions that Conservation & Community Forestry staff at Holden have been asking for many years, resulting in a cycle of research and adaptive management. Young forest is too important to ignore! Here are some things we have been working on and have discovered:

1.) Research and monitoring suggest that bird and bat populations and diversity respond positively when there are gaps of light where young forest and shrubs are growing in or adjacent to mature trees. This can be achieved by ‘edge feathering’ or strategic tree girdling (more on these practices in our Small Woodland Management Manual).

2.) One way to create healthy young forests is to restore existing invaded or weedy large light gaps. Sometimes we encounter large areas in forest interiors where young forest could get a toe-hold but is suppressed by invasive shrubs or grapevine (which, though native, can cause issues of tree deformation and smothering when over-abundant). Our Conservation team has begun a large-scale effort to rehabilitate these areas by removing these vines and shrubs, and the young shrubs and trees—as well as the wildlife who use them—are beginning to respond.

3.) Old pastures and meadows don’t need to be mown for all eternity, nor do they need to be abandoned! Adjacent to Working Woods, two meadow areas totaling around 5 acres were selected for restoration and enhancement of young forest. In both scenarios, one final mowing was followed by a concerted effort to cut back and treat invasive shrubs with herbicide, and in some spaces, this was accompanied by dense planting of native shrubs and trees. These areas have required follow-up herbicide treatments in the order of 5 person-hours per acre per year. 3 years later, both areas have shown increased wildlife activity and extensive use by birds. Michigan lily, native holly and maleberry have surprised us, springing up it seems from nowhere. Dogwood are crowding in the spaces between plantings and native tulip poplar, maple and ash are shooting up while red oak in neighboring wood line are dropping acorns into the meadow edge, resulting in baby seedlings. In short, the combination of invasive species management and planting are both good tools in the ecological restoration toolbox when it comes to managing old-field succession.

Eventually, young forests get older. Then, we will need to ask ourselves the question of when the right time may be to intervene with an intentional disturbance and which areas to allow to grow to maturity. Until then, we will continue to nurture the precious messes of young forest in the Holden natural areas and encourage others across Ohio to do the same.