Holden’s Bat Detectors Reveal (Almost) All of Ohio’s Bat Species Live at the Arboretum

October 23, 2023

Bats are among the most fascinating and most misunderstood animals in the United States. For years, fear of rabies, old wives’ tales, and other myths led to the persecution and active destruction of bat colonies. For a time, the situation improved as conservation organizations worked to educate the public about the intrinsic and ecological value of bats. And then white nose syndrome arrived on the scene.

Hoary Bat is what I find to be the most striking bat species in Ohio and one that we find regularly at Holden (credit: Daniel Neal, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons).

White nose syndrome is a fungal disease first reported in New York in 2006. It swept quickly across the United States, reaching Washington state by 2016. The fungus that causes WNS prefers cool, dark, damp conditions, which means it does very well in the kinds of places that bats choose to hibernate, like caves and mines. This also means that not all bat species are affected equally: Non-hibernating bats, such as hoary bats, have not been affected. But colonial hibernating bats, like the little brown bat that was once among the most abundant mammals in Ohio, have experienced massive declines — more than 90% mortality at some hibernacula.

In an effort to better understand the bat community at the Holden Arboretum, we started a bat monitoring program in 2016. In eight years of monitoring, we have collected and processed hundreds of thousands of bat calls from across Holden, discovering almost all of the bat species known in the state. The presence of these bats show that the Holden property provides healthy forests with a diversity of tree species and standing dead trees, a variety of water sources, and open spaces for foraging, all of which are important to bats.

Detecting bats at the Holden Arboretum

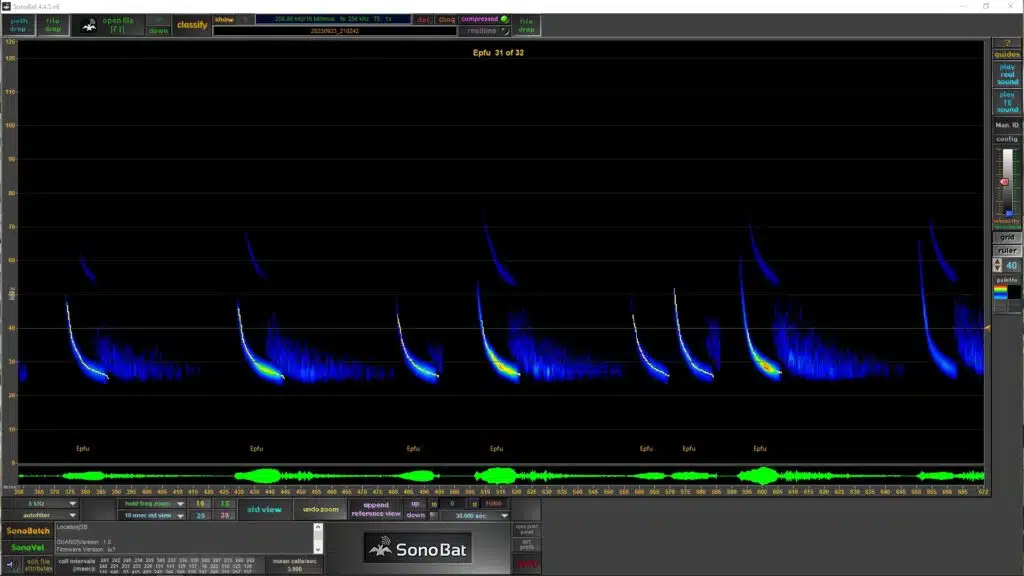

Unlike birds, bats cannot easily be observed and identified visually. However, like birds, bats make a variety of vocalizations that can help us identify them. Most bat vocalizations are ultrasonic – too high-pitched for us to hear. Special devices call bat detectors are designed to listen for and record ultrasonic calls. These recordings are then processed using software that looks for distinctive features of each call and suggest likely species identity.

Our initial surveys focused on a diversity of locations and habitats within Holden’s natural areas, so we could learn how bats use our landscape. Then starting in 2018, we began to focus on bat activity and diversity in Working Woods and other forest management areas in Pierson Creek Natural Area and Baldwin Natural Area. Annual monitoring in these managed woods tells us if and how the bat community responds to the various forestry treatments being used. We also monitor bats in areas where the forest-to-field edge is ‘feathered’ to create a gradient in habitats including field, early successional shrubby habitat, open forest, and closed-canopy mature forest. And in 2023, we started monitoring fields that will be managed to create and maintain early successional habitat.

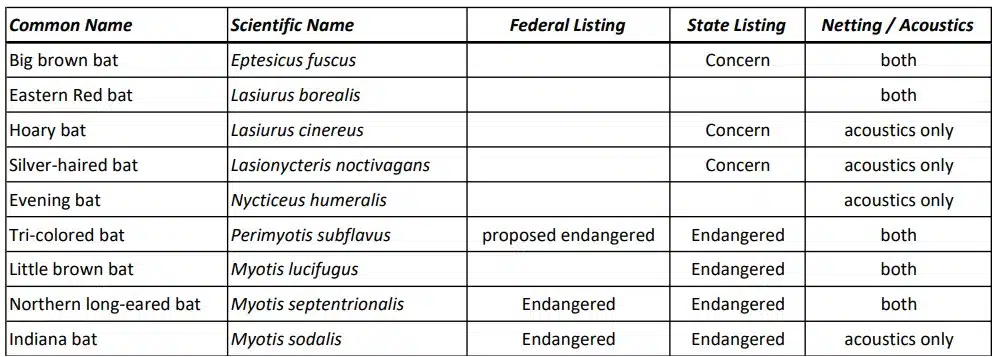

We’ve found nine bat species at the Holden Arboretum, listed in table below from most to least number of recordings. Our acoustic monitoring doesn’t directly measure abundance since we cannot distinguish individuals; rather it tells us diversity and activity level. The table also shows listing status at the state and federal levels, showing that most of Ohio’s bats face serious threats.

Insights into Holden’s bat community

Our acoustic monitoring program has provided several insights into the bat community that uses Holden’s property. The surveys revealed the presence of several species that had not been previously found during mist netting surveys, confirming that the bat diversity at Holden represents nearly all of Ohio’s bats. This demonstrates that our diverse, high-quality habitats are important to bat conservation in northeast Ohio.

We also discovered just how rare little brown bats have become at Holden. During mist net surveys in the early 2000s, roughly 40% of all captures were little brown bats. Acoustics surveys generally find that only 1-2% of all recordings are from Myotis bats, the group that includes little brown bats.

Early analysis of our acoustic surveys also indicates that bats increase foraging activity in areas where the understory is thinned and the canopy is disrupted, like in the southern portion of Working Woods. This forestry treatment is designed to mimic natural disturbances, increasing light on the forest floor (which results in rapid plant growth) and creating structural diversity at the landscape level.

Finally, acoustics can help direct our bat conservation efforts. Three years of monitoring in the forests west of Kirtland-Chardon Road found relatively high Myotis bat activity, suggesting nearby roosts and possibly maternity colonies. This spring, we worked with an Eagle Scout to install two artificial roosts designed to mimic dead trees — a favorite roost of many Myotis bats — in the Fisherman’s Ponds area. Our hope is that these will be used by female Myotis bats to raise their young, in the same was as nesting boxes have helped increase the local bluebird population.

Learn more about bats

We’ll continue to monitor bats at Holden and find ways to incorporate their needs into our management planning. If you’re interested in learning more, here are some great online resources:

- Ohio Bat Working Group (https://u.osu.edu/obwg/) – Lots of great information about bats in Ohio.

- Bat Conservation International (https://www.batcon.org/) – The gold standard of bat conservation organizations and a great way to learn about the ~1,000 species of bats in the world.

- Bat Conservation and Management (https://batmanagement.com/) – A great resource to learn more about bat houses, acoustics, and more.

- White Nose Syndrome Response Team (https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/) – Lots of information about the disease, maps, and more.

Mike Watson

Conservation Biologist

Mike has been the Conservation Biologist at Holden since 2007. His work focuses primarily on wildlife issues such as bird and bat surveys, conservation efforts to support species and/or communities, deer population management, and human-wildlife conflicts. Specific projects include coordinating Holden’s nest box program to support a variety of native cavity-nesting bird species, tracking changes in bat activity in response to forestry treatments, and tracking seasonal movements of the local breeding population of dark-eyed juncos. Mike also assists with non-wildlife projects, including beech leaf disease assessments, deer browse impacts to native vegetation, and hemlock woolly adelgid monitoring.