Rhododendrons are loved by many gardeners for their bright, kaleidoscopic spring flowers. They are special for many reasons, including rhododendron being one of the most species-rich genus of woody flowering plants comprised of over 1,000 species. Their diversity makes them highly suitable for use in scientific studies.

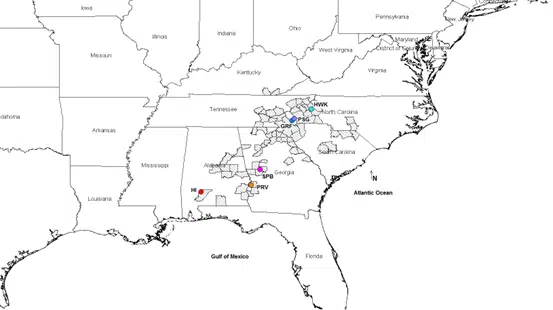

One research project that the Medeiros Lab has been working on is assessing Rhododendron minus (R. minus) from 6 different sites across the geographic range for the species (see map below). Seeds were collected from plants growing in colder, high-altitude environments in North Carolina as well as from hotter, humid environments in Georgia and Alabama. Data was also collected on how plants from these different locations respond to freezing temperatures.

We found that plants from North Carolina suffer less damage from cold weather compared to those from Georgia and Alabama, but the plants from the warmer places grow faster. These physiological differences suggest that plants from North Carolina have adapted to cold temperatures, while those from Georgia and Alabama are adapted to warm temperatures. However, we still need to know if there are genetic differences between the plants from these locations before we can really say there has been adaptation to temperature.

Through our research, we found that genetics, or the study of DNA can be tricky on rhododendron. Rhododendron leaves are rich in yellow chemical compounds known as tannins, and we also encountered an unidentified ‘goo’ in our extractions. These substances interact with extraction chemicals to block the reading of DNA. Since tannins are a well-known problem, techniques exist to remove those compounds. But we didn’t find any information about the mystery ‘goo’ recorded in literature, so we had to ask ourselves if we were doing something wrong.

As it turns out, we can get DNA from rhododendron leaves, but this results in a low-quality product that contains only very short DNA fragments not suitable for newer genetics techniques. Luckily for us, there is an old-school technique, microsatellites, which relies on short fragments to determine genetic relatedness allowing us to move forward in our analysis despite the problems created by the ‘goo’.

Microsatellites – what are they?

Microsatellites are small repeat fragments of ‘junk’ DNA – meaning that the fragments don’t contain genes but are inherited and passed down through generations. This makes them powerful in helping to tell us the relatedness of individuals. The process we’re working with is like the process you go through if using Ancestry or 23andMe to find your closest living relatives. If the plants we studied from cold locations are genetically different from the plants from warm locations, this will suggest that there has been evolution for cold hardiness in the cold populations and heat tolerance in the warm populations.

We recently arrived at a milestone for this project and received our fragment analysis results. Our next step is to analyze the results with analysis software. So, the question one may be asking is why is any of this important? The abbreviated answer is – in a world where climate change discussions are prevalent –this information can be used for selecting and breeding species with adaptive traits suitable to meet future demands. Some of this type of work is being done by Connor Ryan’s team at Holden’s David G. Leach Station in Madison. We’ll post updates as we work through the next phase of this this R. minus research. Enjoy this season’s spring blooms and stay tuned!

Map showing our R. minus seed and data collection sites in the Eastern United States, hashed regions of the map show all the counties where this species occurs, colored dots show the six collection locations, including Hawksbill Mountain, North Carolina (HWK), Mt. Pisgah, North Carolina (PSG), Graveyard Fields, North Carolina (GRF), Sprewell Bluff Wildlife Management Area, Georgia (SPB), Providence Canyon State Park, Georgia (PRV) and Haines Island Park, Alabama.