How Data-Driven Conservation Fledged 30,000+ Native Birds at Holden Arboretum

May 5, 2025

The bluebird program at Holden reached a milestone in 2024: 60 years of continuous conservation and data collection. This history is marked by clear successes in the effort to support native cavity nesting species, as well as numerous challenges, many of which we are all very familiar with. For a program to continue for 60 years (or even 10) it is important to make regular and careful reviews of the program and consider possible improvements. Although it seems like common sense to identify problems and find solutions, and we all do it in almost all aspects of life, I think it’s important to highlight the value of data collection as a way to help identify problems, determine solutions, and then test to see if those solutions actually work.

Holden’s dataset is large: 13,611 nest attempts, each with data from twice weekly visits. Over the years, we’ve mined that dataset for ways to address common challenges, including sparrow management, nest parasite impacts, and nest box design. The process was relatively simple for some issues: if we change sparrow management strategies, do we see less mortality in the following years? Others included more detailed analysis to understand the causes and solutions to certain problems.

Here I’m going to discuss two of the more detailed examples as a way to show the value of data collection and analysis and to encourage everyone to continue thinking about and sharing ways to improve our conservation efforts.

Predator Management

When I started with Holden’s program in 2007, we had some standard strategies to reduce predation: don’t mow dead-end paths to nest boxes, remove material from the bottom of very tall nests to make it harder for a predator to reach eggs/young, and mounting boxes only on metal poles. There was also a policy of applying axle grease to poles to make them harder to climb and a handful of cone and Noel guards scattered across our 200+ nest boxes. However, axle grease was not used uniformly and often failed to prevent climbing predators and in 2007 we experienced extensive predation across all trails; fledgling numbers were less than half the previous season’s. This prompted us to ask how nest success was affected by the presence and type of predator guard. The results made it clear that unprotected/axle grease boxes were much less successful (49% nest success) than boxes with either cone or Noel guards (60% and 66% respectively). A review of information provided by OBS, NABS, online resources, and talking with other bluebirders pointed us to the Kingston or stovepipe style baffle as being effective and relatively cheap and easy to build. We built and installed baffles for all our boxes and watched nest success jump to an average of 74% over the next 5 years.

I find this example to be valuable for several reasons. First, it highlights the importance of predator protection for all nest boxes and that years of low predation are no guarantee that you won’t have problems in the future. Second, it demonstrates how data can be used to justify the time, effort, and cost of making changes to a big program. Our analysis helped us acquire the funds needed to build and install the baffles. And finally, our results support other people’s assertions that the stovepipe/Kingston style is a very effective predator baffle. Although there are a variety of baffles and guards, our experience points to the stovepipe style as more effective than cone or Noel guards, and I encourage anyone who is ready to install new baffles to consider this style.

House Wren Management

Just a few years after installing the predator baffles, we decided to address the increasing number of house wren attempts at our nest boxes. As a native species there are limits on what kinds of strategies can be used to deal with wrens. And the scale of our program made some options (e.g. wren guards) not very practical. However, knowing that wrens generally prefer shrubbier habitats suggested that nest box placement could be a factor to consider. New trees are planted, tree lines creep into fields, and some areas are allowed to grow shrubbier over the years, potentially making them more attractive to wrens.

For this, we turned to our GIS mapping and used the software to classify nest boxes into categories by how far they were from the nearest tree line. We found a statistically significant effect of distance on choice of nest box. Wrens used boxes within 25 meters of a tree line more than expected and avoided boxes further away. Bluebirds, however, showed the opposite preference – using boxes greater than 25m more than expected and generally avoiding closer boxes.

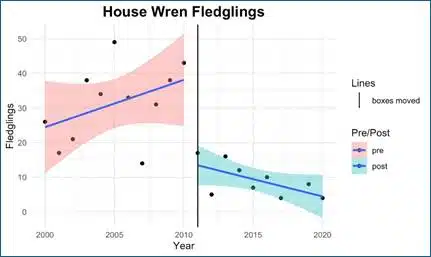

As with the predator example, this analysis provided justification for the effort of moving those boxes that were located less than 25m from a tree line (~20% of our boxes). In fact, subsequent analysis shows that the increasing trend in wren fledglings switched immediately to a decreasing trend in the years after we moved those nest boxes.

We’re now nearly 15 years since that original analysis of nest box placement and we’re starting to see increasing wren numbers, suggesting it’s time for a new analysis to identify which boxes should be moved.

60 Years of Success

Holden’s program started when a group of volunteers asked permission to install nest boxes on Holden property in the early 1960s. Since that time, volunteers have monitored and maintained more than 200 nest boxes and assisted with banding all native young in the nests. In many cases, their observations while in the field are vital to identifying problems and developing solutions. Boxes have been moved, trails have been decommissioned, box styles have changed, and many other modifications have been made in 60 years to keep the program running successfully. Whenever possible, we use our data to support and guide those changes to the program.

There are several metrics I use to define success for Holden’s bluebird program. First is the number of native species we have fledged. In 60 years, more than 30 thousand birds have successfully fledged from our nest boxes. More importantly, though, the annual numbers have increased dramatically, indicating a recovery of the bluebird population. During the first 10 years, Holden fledged an average of 56 bluebirds per year. During the past decade that number is nearly 400. The story is similar for Tree Swallows, which usually come in a close second in terms of annual numbers.

| Species | #Fledged |

| Eastern Bluebird | 14445 |

| Tree Swallow | 11939 |

| House Wren | 3209 |

| Purple Martin | 580 |

| Black-capped Chickadee | 258 |

| Tufted Titmouse | 7 |

| Total All Native Species | 30438 |

I also consider the long history of volunteer involvement as a measure of success of the program. Not only are they vital to the continued existence of our program, but Holden’s program provides a valuable connection to nature and a learning experience for those volunteers.

Finally, by collecting, using, and sharing data, the program is contributing to a much larger conservation effort. All data since 1965 have been submitted to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (NestWatch), adding to a large and scientifically valuable dataset that has been used in hundreds of publications.

I encourage everyone, regardless of the number of boxes they monitor, to keep careful notes and take time to review them at the end of the season. Share your experiences and successes with others in the community and send your data to OBS and NestWatch to support larger-scale conservation of native cavity nesting birds.

This article was originally published in the Ohio Bluebird Society newsletter, and co-authored by Rosana Villafan.

About The Ohio Bluebird Society

The Ohio Bluebird Society is a non-profit organization founded in 1987 to support Eastern Bluebirds and other native cavity-nesting bird species. OBS tracks bluebird success via fledgling reports from its 300+ members and has documented nearly 140,000 bluebirds fledged in Ohio in just the past 25 years. Holden’s long history with bluebird conservation means frequent collaboration with OBS, including Holden staff and volunteers in leadership positions within the organization. In 2006 Holden received OBS’s Wildlife Conservation Award to recognize the long history of bird and other wildlife conservation efforts at Holden. Currently, Holden acts as the organizational host for OBS.

https://ohiobluebirdsociety.org/ to learn more.

Mike Watson

Conservation Biologist

Mike has been the Conservation Biologist at Holden since 2007. His work focuses primarily on wildlife issues such as bird and bat surveys, conservation efforts to support species and/or communities, deer population management, and human-wildlife conflicts. Specific projects include coordinating Holden’s nest box program to support a variety of native cavity-nesting bird species, tracking changes in bat activity in response to forestry treatments, and tracking seasonal movements of the local breeding population of dark-eyed juncos. Mike also assists with non-wildlife projects, including beech leaf disease assessments, deer browse impacts to native vegetation, and hemlock woolly adelgid monitoring.